A few days ago we ate at our favourite restaurant for the last time. A fixture on the Wellington dining scene since it opened eight years ago, Field & Green has now closed its doors for the final time. We aren’t the only ones who will miss them, even though, living mainly away from the city for a while, we don’t visit as often as we used to. But the last few years have been challenging in hospitality so the news, although sad, isn’t surprising.

It feels as though they’ve been around forever, and it certainly seems longer than eight years ago we first ate there, which tells me it must have been in their early days. Confession: my memory of that visit isn’t the food, although I presume it was as impressive as it usually is. What I remember is casually lifting the knife, noting that it wasn’t your standard chunky mass-production full-stainless-steel with the handle morphing into the blade. Instead its steel blade – non-serrated, long and flat with a rounded end – was secured onto a pale yellow handle, itself long and even. It was a knife like the kind I grew up using and a tsunami of memories pulled at me before crashing me back to the present. I peered at the faded inscription on the blade to confirm my suspicion: it was Sheffield-made.

‘Look!’ I almost yelled. ‘They’re from Sheffield!’

A little history here. For a long time Sheffield was the home of stainless steel, particularly cutlery. The many steelworks lining its rivers were the lifeblood of the city, with thousands of workers – including my grandfather – entering and leaving those huge buildings day after day for the greater part of their lives. In terms of fine stainless steel, Sheffield was synonymous with quality and anything made elsewhere was inferior. For this reason, if the word didn’t appear on a piece of cutlery, it wasn’t crafted in Sheffield. Much like the best ham, or cheese, or wine, in the world, we had DOC status. If the knife you are holding has Made in Sheffield, or similar, stamped on it, maybe written in shaky engraving, you know you are holding a piece of quality and beauty. If it has a bone handle, you know you are holding a piece of history.

To see these in a restaurant is rare. Bone-handled knives and EPNS forks and spoons have to be handwashed because dishwashers destroy them. They may have been ubiquitous in high-class establishments in the past, but you don’t generally find them in the twenty-first century in a small restaurant twelve thousand miles away from the place they were created.

A few weeks later I suggested a friend join me for a birthday lunch at this great new restaurant. We sat at the chef’s bar and I picked up a knife to show her, exited to share a bit of my home city. This one said Firth Brown and I squealed.

‘That’s where my grandad worked!’ I said as I stared at the knife.

The squeal alerted the attention of a lady in white with a black apron. She paused and looked at me, possibly sensing a customer satisfaction issue. My friend laughed and repeated my words. The lady introduced herself: she was Laura, the chef and co-owner; the cutlery was the responsibility of her partner, Raechal, some of it passed down through her family, some of it acquired after hours of scouring second-hand shops and online markets. Gobsmacked on my first visit, I was almost struck dumb on my second. Almost. To be honest, I went into only-dogs-can-hear territory, words screeching incoherently from my mouth. Laura smiled politely and backed away from this strange woman armed with cutlery.

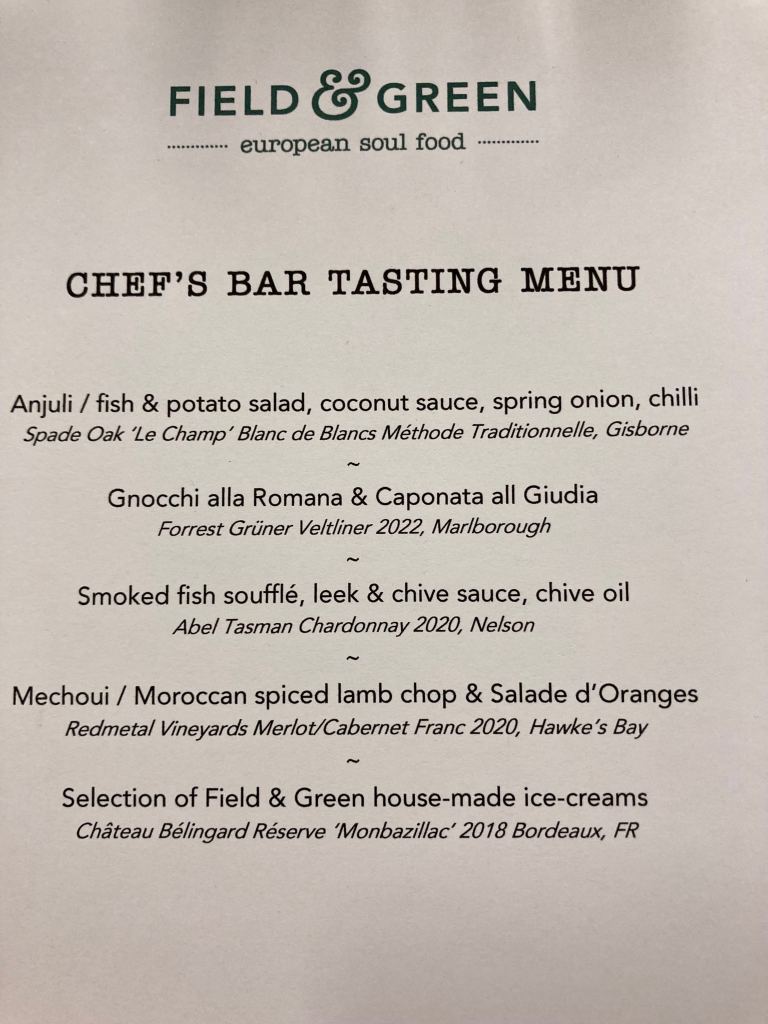

I can’t count how many times we’ve been to Field & Green, but I know we’ve never left feeling less than impressed. Laura describes her food as European Soul Food – all I know is it’s always damn good. The menu is small and changes regularly, although there are some items that are constant (the brunch kedgeree was the best in the city). For the annual Wellington on a Plate food festival they upped the ante, converting the restaurant each year to focus on one region and featuring dishes from the Jewish diaspora. Courtesy of them we’ve visited Greece, North Africa, Brick Lane in London, and India, each time rolling out the door stuffed and our mouths still zinging with the incredible flavours we’ve just tasted.

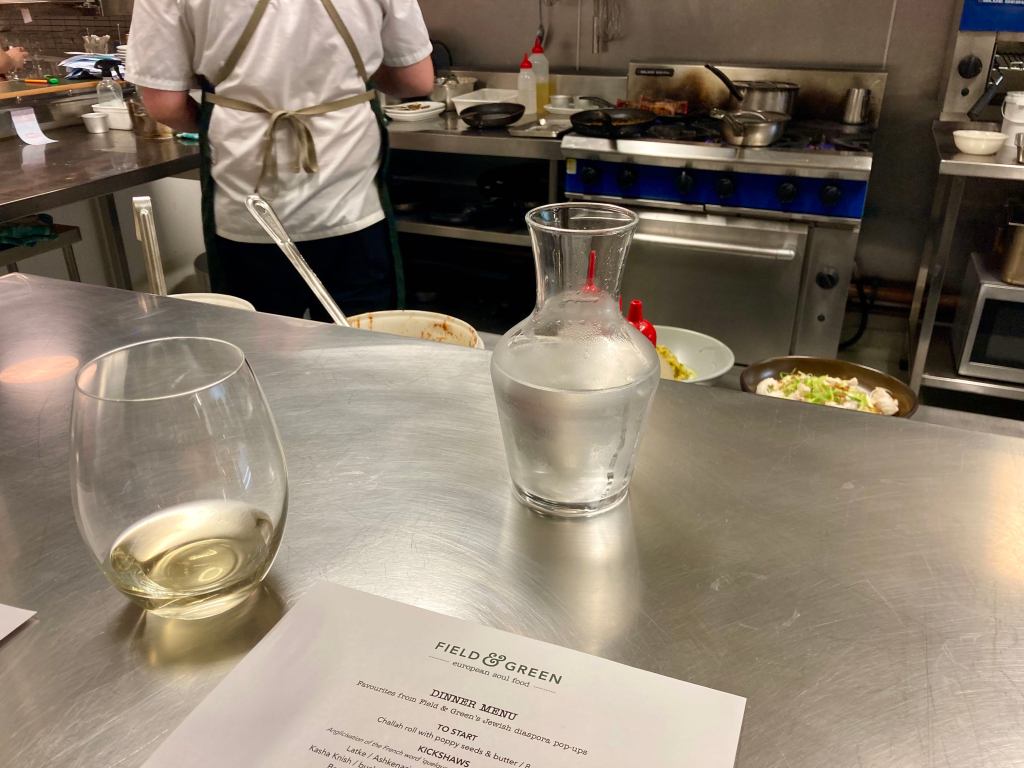

This last time we sat at the chef’s bar, a long strip of stainless steel (inferior to the cutlery placed upon it) watching chefs put the finishing touches to a plate about to land in front of a salivating diner. I use finishing touches deliberately – as a mere home cook I know how long it can take in preparation to get a dish anywhere near ready for actual cooking, let along chucking it – in my case, carelessly – on a plate. I made a moussaka recently, laughing at the prep time of thirty minutes – a friend makes an excellent version and I’ve been there as he chopped, fried, baked and layered for most of the afternoon, and I’m no quicker. Probably one of these chefs would casually knock it out in half an hour whilst simultaneously preparing a dessert and starter. I sit in awe at this bar.

I could make an effort to re-create some of the magic at home – Laura admits that many of her recipes originate, or are inspired by, Claudia Roden’s tome The Book of Jewish Food and I have this on my shelf. I’ve even used it a few times, or recognised a similar recipe to one I’ve used from another, more recent, cookbook. (I once searched the index repeatedly, wondering if my eyesight or my mind had gone because I couldn’t find any recipes for pork meatballs. My mind, obviously.)

We – and many others – will miss Laura’s amazing food and her smile as she waves from the kitchen or pops out to say a quick hello between feeding the hungry hordes, but I doubt anyone will begrudge her and Raechal their break. As they wander into the sunset with their cute little dog, I hope they realise what an impact they have made on the Wellington culinary scene and on the lives of those who ate there. We wish nothing but the best for them, even if we do rather selfishly hope that it involves serving food to hungry Wellingtonians (or in any other location – we’ll travel!) But we’ll understand if they’ve had enough of that.

Shalom!

I grew up with similar cutlery and now Iam wondering if it came from your home town.

LikeLike

It possibly did! Early settlers would have brought it with them and it was built to last.

LikeLike

Your attachment to the cutlery of your childhood reminds me of the Laguiole knives produced in France, which trigger the same attachment to a long tradition of excellence that can be found all over the world.

LikeLike

Coincidence: we have good friends who live in Aveyron. When they visited NZ we ‘discussed’ whose cutlery was better. In balance, we now have Sheffield in one house and Laguiole in the other. No idea what we would do if we sold one house!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m impressed that you know Laguiole so well, it’s an origin that’s regaining notoriety.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Took me back to being at home eating with these knives and forks, and definitely great memories of growing up.

Wouldn’t change them for the world.

Can’t beat Sheffield Steel.

Love you n miss you xx

LikeLike

Absolutely! Love you back xx

LikeLike